Discover the Secrets of the Rolling Stones with Bernard Fowler: A Deep Dive into Rock History!

The Rolling Stones have just released their first album of new material in 18 years—Hackneyed Diamonds—but during that fallow period one of their longtime bandmembers, not of British descent, released his own studio album. During the spring of 2019, I was talking with drummer and producer Vince Wilburn, Jr. for a piece on the previously unreleased album by Miles Davis from the ‘80s. Ever the musical evangelist, Vince said that I had to hear this album he’d played on by the singer and percussionist Bernard Fowler, who has been touring with the Rolling Stones as a backing singer for decades. “He does Rolling Stones tunes,” Vince said excitedly. “But you’ve never heard them like this before.” Really? It just seemed like b.s. given that jazz singers doing Rolling Stones tunes almost always just sounds silly, no matter how original or stylish they think they are. When you take the persona and the band sound out of those tunes, it can sound like some lounge act. Vince laughed when I told him my apprehension. “Oh, you’ll see.”

I did. Soon enough I was the excited evangelist talking to people just like Vince talked to me because Bernard completely reinvented the songs as spoken word pieces with raw jazz and percussion underpinning. Many people don’t even recognize the songs as Jagger-Richards originals.

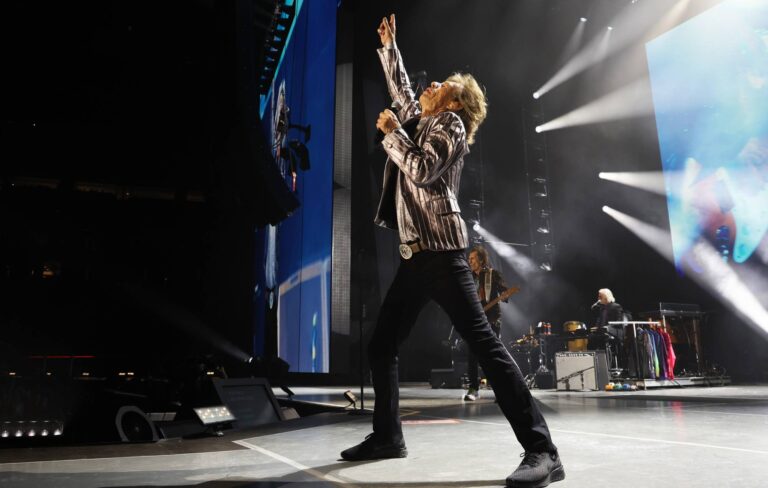

Bernard is a living example of how some gifted artists, whether they be singers or instrumentalists, use their talents to lift up others, but yet have their own projects on the side, which often are ignored or dismissed. I have played the album for many people and everyone has been knocked out. Even Don Was, who has been producing the Stones for many years, was captivated when he heard it while we were hanging together at the Monterey Jazz Festival. The album could have and should have been a bigger story but it was released just as Jagger had a heart condition which necessitated the postponing of their appearance at Jazzfest in New Orleans and their tour. His health, recovery and return to the tour made any other story around the Rolling Stones superfluous at the time. To their credit, the Stones did play the album before some of their concerts during that tour. However, it’s entirely possible that the thousands of fans at the concerts didn’t recognize the songs either.

Bernard Fowler has been a backing vocalist for numerous artists and bands, including David Bowie, Material, and Alice Cooper. But it’s been his long-running association with the Rolling Stones that has sustained and inspired him. He’s been touring and recording with the Stones since 1988, so it should be no surprise that the veteran singer elected to focus on Jagger-Richards material for his third album, Inside Out, on Rhyme & Reason Records.

However, there is a surprise: He doesn’t sing on the album, at least not in a strict sense. Instead, Fowler approached the songs as spoken-word pieces backed mostly by percussion, evoking the Last Poets, Amiri Baraka, and Gil Scott-Heron. The result is a fascinating exploration of Jagger’s words removed from their often iconic musical associations. Stripped down to bare essentials, the lyrics sound decidedly dark and hypnotic. Fowler indeed has turned the Stones’ music inside out.

The idea for the project started several years ago during a tribute to the Rolling Stones at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame at which Chuck D from Public Enemy was supposed to perform. Chuck D missed the flight and Fowler did “Sympathy for the Devil,” reciting the lyrics as spoken word. The idea became implanted in Fowler and became more realized a few years later during a rehearsal for the Zip Code tour in 2015. “I was just messing around playing conga and Chuck Leavell comes onstage and says, ‘We gotta try this song for the soundcheck,’” explains Fowler. “I started reciting that tune in spoken word. Keith and Mick and the guys were looking at me, smiling. At some point I’d been doing it every day and Mick said to me, ‘You know, Bernard, I’ve heard Rolling Stones songs done a lot of ways, but I’ve never heard it like this before.’ And I told him that when the tour was over, I was going to cut it. He said, ‘You should.’ And I did.”

The influence of African-American poets and spoken-word artists such as Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, and the Last Poets on Fowler was no coincidence. “When I was growing up there was a show on PBS called Soul! and during that show they had a lot of new acts like Earth, Wind & Fire, before they got big,” explains Fowler. “Amiri Baraka and Nikki Giovanni also used to be on that show reciting their poetry. I grew up hearing that, as well as the Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron, whom I had the privilege of working with.” Fowler did one album with Scott-Heron that Bill Laswell produced, singing on a song called “Reron” about then-President Reagan-For the accompanying percussion that forms the backbone of the new album, Fowler asked Walfredo Reyes, Jr., Munyungo Jackson, and Lenny Castro to bring their roots in Puerto Rico, Cuba and, yes, New York City to the fore. “When they’re playing drums, it’s the same dialect,” he explains. Fowler, who also plays percussion with the Stones, joined the studio drum circle on many of the tunes. “I could not have all those cats in there playing and not get my hands dirty too,” he says, with pride.

Fowler grew up in the Queens Bridge Projects in New York, where Latin percussion formed a virtual soundtrack. “When I was growing up, there was always drums in the neighborhood in the park—I woke up to that, I went to sleep with that,” he recalls. “With this project I was originally only going to use percussion. There were not going to be any of the instruments except percussion and voice. As things progressed, I started to hear other things and I decided to use a rhythm section on a few of the tracks.”

The rhythm section he did add included some old friends from common paths and bands. Drummer Steve Jordan played with Fowler in various New York avant funk and rock bands in the ’80s and also has had a close relationship with Jagger and Richards for many years. Vince Wilburn, Jr. and the bassist Darryl Jones come from Chicago and both are alumni of Miles Davis’ groups. Of course, Jones is the current bassist for the Rolling Stones, and has been since Bill Wyman left in 1993, even though he is rarely pictured with the group.

For the funky rhythm guitar licks, Fowler turned to Chicago-bred players George Evans and Ray Parker, Jr. Yes, the latter is the same guy who scored a hit with “Ghostbusters.” On this album, Parker reminds us of his very real gifts as an R&B instrumentalist before his mega-success as a pop vocalist. “When I was recording it with the rhythm section, the only instruction I gave was that I wanted it from a specific era,” Fowler says. “They’re all from Chicago, so they knew exactly what I was talking about. They played many grooves. They played grooves until I told them to stop.” Those ’70s-style grooves work perfectly with the percussion and support Fowler’s recitations of Jagger’s often otherworldly lyrics.

Having performed with the Rolling Stones for all those years and having sung so much of the material, Fowler himself was certainly very aware of the lyrical detail, but he was fascinated by how little even the most seasoned musicians and music lovers knew about Jagger’s words. “What struck me was as I was working on this idea was how so many Rolling Stones fans don’t understand how heavy some of the lyrics are,” he explains. “They get lost in the rock and roll.”

Recording the album at the Stakehouse, a local studio in L.A. he calls home, Fowler kept the tracks under wraps for a long time. Until he decided on a little focus group of sorts. “One day I invited some players who were working in other rooms to come and listen to a song,” he says. “These were stone-cold rockers too. They were like, ‘Bernard, this is incredible.’ I was waiting for someone to say something or recognize it. Finally, I said, ‘Do you get it?’ None of them had any idea what they were listening to. When I told them [that it was a Rolling Stones tune], they freaked out.” Jagger’s tendency to distinctively slur or mumble the words may have contributed to the confusion, but it’s true that Fowler’s approach renders the material much less opaque.

However, even Fowler admits to being surprised sometimes by the complexity and depth of Jagger’s lyrics. “Sometimes we’d be working on a song and I’d have to learn the lyrics and I’d go, ‘Whoa, those are the lyrics? Wow, these are really strong.’ There was one song in particular that when it was released, I thought was very strong.” The song was 1983’s “Undercover of the Night,” a tune inspired by the war in Nicaragua—and for which Fowler also wrote and recorded a dramatic preamble read by a woman for Inside Out.

“It’s a girl who’s running scared in the jungle during the war,” he explains. “She’s afraid of being caught by the military because they’ll send her to one of the camps. I called the bass player Carmine Rojas, a Puerto Rican brother from New York, and I told him I wanted a girl to speak Spanish, but I realized that every territory speaks Spanish, but in a different way. I told him it’s gotta be a girl from Nicaragua. He called me and told me, ‘I got her, I’m sending her over to the studio and I’ll meet you there.’ They came over and I introduced myself to her, Rachel Morales. She is not an actress. She’s not a vocalist. She’s never been in a recording studio in her life. I gave her the dialogue and I told her what I needed. She was a bit apprehensive because I found out right at that moment that she grew up in Nicaragua during the war. She lived it. So when she went in to record it, she started to cry because it brought up so many memories as she was delivering this dialogue I provided. [Listening to it] the hair still stands up on the back of my neck.”

Another song that might raise some hairs is “Dancing With Mr. D,” which the Stones recorded on their Goat’s Head Soup album in 1973. Recited by Fowler over the stark yet driving percussion, the tune’s lyrics evoke a dark trip to a voodoo priest or Appalachian bootlegger.

And, be honest, would you have recognized those lyrics without the pre-identification? Much the same can be said of Fowler’s versions of “Sister Morphine,” “It Must Be Hell,” “All the Way Down,” and “Time Waits for No One.” About the only song that’s instantly recognizable to the average listener is “Sympathy for the Devil,” whose lyrics have become a part of global pop culture.

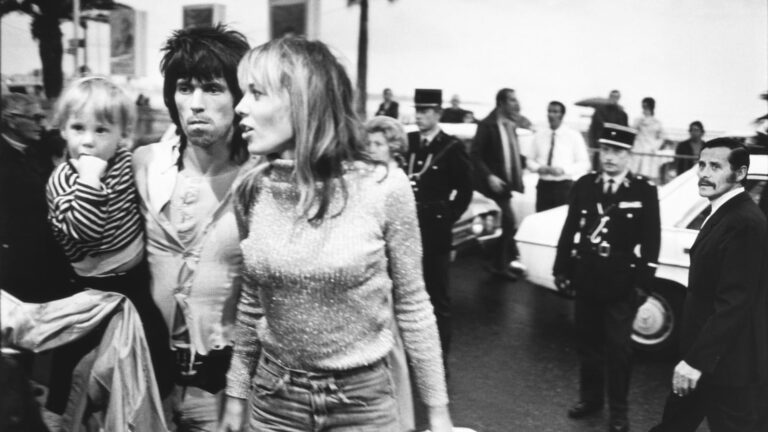

Naturally, we’re all curious as to the reaction from Jagger and Richards. At the time of our interview, Fowler hadn’t been in direct contact with either of them since he finished the album. “I don’t know if the cats have heard it yet,” he explains. “When I first started recording it, I had to go to New York for something. I met Keith and we were at a studio and I told him about it. I played him a rough of a couple of tracks. He looked at me and smiled and his exact words were, ‘Damn, Fowler, you went deep.’”

Fowler wants it made clear that he’s neither exploiting the Stones nor asking them for any support. “I’ve never wanted to do that and I’ve never done that,” he says. “Even all my solo records, I always do them on my own. I did this record myself. I didn’t have a record company backing me. I had absolutely no budget. I called all my friends to come and help me and they all came out. This record allowed me to show my production chops.”

He does hope to do the material live and points to the simplicity of the arrangements as a key factor. “I can do the stripped-down version with two percussionists,” he says. “Straight-up beatnik style.” And the veteran vocalist is also well aware of the irony that this album, on which he doesn’t sing one note, may garner the most attention of any of his solo projects. “I told Vince [Wilburn, Jr.], ‘I’ve been singing my guts out for all this time and it’s going to be a spoken-word record that everybody goes for.’” As Jagger himself wrote, it must be hell.